wordsout

<

family >

I

never shall go back

We

did this

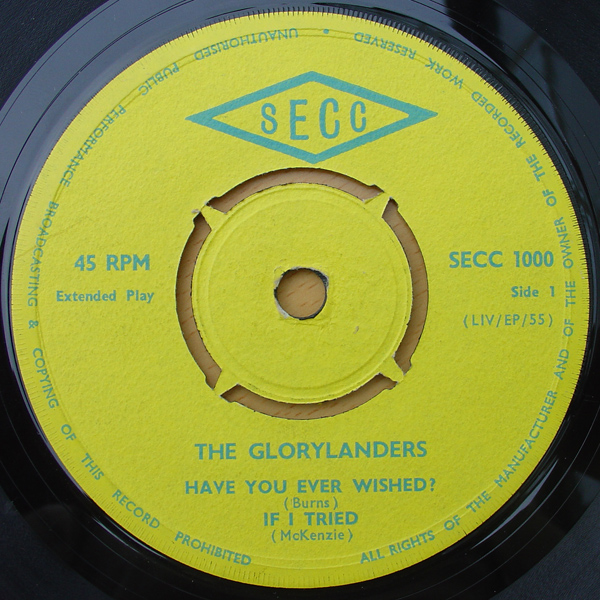

thing on local radio—Ali, me

and Richard, singing Glorylanders’ songs

(Larry Norman too risqué) with zealous voices

and my impossible-to-tune 12-string.

Seven or eight tracks straight off, no retakes—

Teach me thy way, I looked for love,

I never shall go back. From time to time

I got reports that someone heard it

in the God slot—even after a decade

when to be kind the tape should long have been

recycled for a local farming feature—

they played a song on air, and back-announced

That was the Reps from Ilkley, from

1970—

I wonder what those boys are doing

now?

That

would have been the end of it, except

that by a freak of providence the master tape

turned up in the possession of a friend; and

so

a cassette plays in my family estate

on my drive to work, and earnest teenage

ghosts

fill up the car across a quarter of a century:

my seventeen-year old fingers once again

run down the fret-board to infinity.

I

learned guitar at ten. My brother Chris

taught me the first three chords

and so we played—the Minibeats—

in matching polo necks at Harvest Suppers.

Things we said today, You can’t do

that

and our own song, Don’t go away—the lyrics

written by Dave Postlethwaite in an exercise

book

and set by Chris to a tune I thought was fab

(later I found he nicked it from the Stones).

Then came the youth club in the wooden hut

behind the Baptist Church; Crusaders;

Billy Graham; Sunday evening Rendezvous

spent strumming choruses from Youth Praise—

G, E minor, C —Can it be true?

Camps, midnight hikes, romance at

country dancing,

hands holding hands in knowing innocence.

The Sixties raged outside. We bought

the records,

read the rude bits of Lady Chatterley

and sat in the Continental coffee bar

waiting for life to start.

Even so The Reps

were retro, more Bachelors than Beatles,

making our brash assault on draughty halls

as far south as Dewsbury and Castleford

with dodgy three-part harmony. Driving to gigs

in someone's mother's car we belted out

Sankey choruses with the windows down—

When the roll is called up yonder, I'll be

there!—

part meaning it, part mockery, part desire.

We played till college, and our careless choices

turned into separate lives.

The

soundtrack then

was Seventies rhapsody. Bowie, Free,

the Stones—

I've got a silver machine—sweating it out

in flares and strobes at Union discos.

Ch-ch-ch-changes in the coffee bar,

Benson & Hedges 30p for twenty,

tap on the window at the porters’ lodge

if you run out after midnight.

Neil Young, the Eagles, Crosby Stills & Nash

blaring out of Bose speakers rigged up

in the Entertainments office—After

the thrill

has gone—

as we ate our take-aways and thought the world

was waiting just for us to put it right.

Of

course

the rockers overplayed their hand.

Punk tore it down, dance ground it to a pulp,

the bass’n’drums, tuned to mind-numbing pitch,

drowned out the fact that words had lost

their way—

rhythm and pose stamped out on vapid hooks.

The lyric always held the secret: tunes

were scaffolding for words to clamber up on.

From David’s psalms to Robbie Williams’ Angels

the work of these recording engineers—

whose technology was only words and pitch

imprinted on the human memory—

so well encoded phrase and melody

to smuggle in the old nostalgic lie,

the thought that somewhere it may still go on,

those nights spent talking on the brink of truth,

those summers in North Wales where we

lived out

the endless holiday of youth, and we might go

and find them as they were, our icons—

Lennon, JFK—

frozen in time, minding the store of dreams.

The years have laid all this to rest

and now the background music at my desk

and every Sunday worship song I pick

is carefully selected to evoke

a world we recognise, or we can cope with,

learning that life went off on its own way,

that dreams ended in ordinary jobs

and marriages and broken promises,

more careful to avoid those memories

where every blemish, each note held too long,

each mistimed chord or shaky harmony

cannot be overdubbed but still repeats

precisely as that first imperfect take

I punch out of the tape-drive with a stab.

I wonder what those boys are doing now?

Well hey, I’m up here, passing Shepherd’s Bush,

with vapour trails above in a bright blue sky.

I sent a copy of the tape to Alistair

who filed it I expect among his shelves

of sermons and syndicated radio talks.

I sent Richard one, but got no reply. After Paddington

I switch to the CD, leap two decades

into warm harmonies and self-assured percussion,

other voices blending in with mine

and other songs, more crafted, less direct,

all flaws mixed out. I watch from the moving car

a plane fly overhead above an earth

which spins around a sun which moves

towards another star—each of our actions

will be accounted for, nothing that is hidden

is not in some dimension brought to light.

On the last crest of the flyover

a hoarding says with comforting assurance

The future is not something we travel to,

it’s something we build; and I coast down

to Marylebone Road, the sunlight bright

on flashing windscreens as the voices peak

against a soaring saxophone—Where it will lead

God only knows—knowing what I have made,

my marriage, my three children,

this edifice of words, will all survive

the best and worst of me: these are

my sacrifice, my prayer, my daily worship.

I looked for love. I never shall go back.