wordsout by godfrey rust

< all souls >

Not

The Basic Method

A "lecture" at a Core Year weekend away, being a parody tribute to the method of bible study propagated by the Rev Andrew Cornes

Right Ladies and Gents—the most important lecture of the term! All of you who aren’t here, see me after.

Books. For this week, just one recommended: Not The Basic Method by Andrew C J Cornes. Published by Puffin. Unfortunately out of print and written in Urdu but I have one copy imported at a special price of £38.50.

We must begin by asking, how can I discover what the writer meant for his original listeners? To illustrate this approach I would like to give you a short lesson in art appreciation.

This is one of my favourite pictures. I have a copy of this hanging in my room. To illustrate the Basic Method I’d like to describe how I approach a large chocolate or cherry-and-almond cake.

First I will ask the question What is the main subject? Obviously, this picture shows a cherry-and-almond topped cake with a slice taken out of it, sitting on a plate. But this is too much detail, missing the wood for the trees.

Basically, this is a cake. Food. The main subject is food.

Now I ask second, What do the details add? I’ll look at the different sorts of nuts in the cake covering, perhaps count the cherries and density of the raisins inside, and I might ask Why is this slice taken out of it? What does this add to the main subject?

In fact rather than adding to it, this missing slice has unfortunately taken away from the main subject, which would tell me that not only is this food but it is good-tasting food, and some wretched person has got there first and scoffed some of it.

However, before going any further I must ask one more question: What does the setting add? Is this just one cake or are there others competing for my attention? How long has it been on this table? Are there people standing around who are likely to notice how large a piece I take? All this will add or detract from my appreciation of the main subject, which I must never lose sight of.

So you will often see me at restaurants or tea parties, first standing back, then going close trying an almond or a finger or two of icing, then standing up on a chair taking in the whole scene, checking the chef’s fingernails, how clean is the tablecloth, seeing the nice men in their white coats coming in with the straitjacket— and only then, when I’ve really got to grips with the subject I’m dealing with do I move on to the most important part—the application of the main subject and all the details.

This is the sort of approach we must use with biblical texts if we are to apply them properly, First we sort out the main subject, then see what the details add. We look at the details in two parts— words and grammar.

Words. In general you’ll need a good concordance, commentary, dictionary and bible atlas, especially dealing with the Old Testament, if you’re really going to grapple with the meaning of the text as its original readers would have understood it.

For example, take a well-known text from the Old Testament, the Song of Solomon, chapter 7 verse 4: Your nose is like a tower of Lebanon, overlooking Damascus. You would probably assume this is quite a normal metaphor, the writer paying his lover a straightforward compliment.

However, any good commentary will tell you that the word tower does not here refer to a tall building, but a tow-er or puller, a person who tows. You will be aware that in Solomon’s time, when this verse was written, a great deal of cedar was sold to Solomon by the King of Tyre. The Bible, however, is silent on the means of transport by which the wood made the 120-mile journey. Contemporary documents tell us that the King of Tyre employed a great deal of casual labour—giving us the derivation of his name, Hiram—to drag the wood to Jerusalem. These men became a contemporary phenomenon and were well-built Nubian eunuchs who were generally referred to as the towers of Lebanon.

Another consequence of this booming trade with Solomon was that Hiram was unable to supply another neighbour, Damascus, with sufficient quantities of cedar for their needs. Damascus therefore felt ignored, or as the Bible writer puts it in this phrase, overlooked, and frequently set off to smite both Tyre and Israel with the edge of the sword. As a consequence the tow-ers had to move as fast as they could to try to stay out of the way of the Damascenes.

So with this new insight we can see that in this phrase, far from paying his lover an innocent compliment, the writer is suggesting that her nose is in fact large, black, constantly running and the cause of frequent strife and dispute. Without a careful study of the words we would never have grasped the real meaning of the text and would have gone on to make an entirely inappropriate application of it.

Now we must move on to structure, and a brief lesson in grammar. Each sentence divides into two kinds of pieces, the set piece and the companion piece or pieces.

For example, take the verse Exodus 17 verse 12, But Moses hands grew weary so they took a stone and put it under him, and he sat upon it, and Aaron and Hur held up his hands, one or one side and the other on the other side.

This is a very clear illustration of set and companion pieces. In the first part Moses is tired so the others set him down on a rock, which clearly makes this the set piece. The remainder tells us what happened to Moses’ companions Aaron and Hur, and so this is obviously what we call the companion piece.

Each companion piece answers a question posed by the set piece. Now last year many people were confused about how to identify the different kinds of companion pieces, so this year I’ve put down five simple rules which you can apply to find out which question each companion piece is answering. The rules depend on the word at the beginning of the piece.

1. “In” always answers a when? question except when it answers a where? question, or in the case of the phrase “in case” in which case the question is why?

2. “Because” answers the question why? as does “as”, because as and because normally mean the same, that is, “for”.

3. “Which” answers what sort of? and “so that” with what result? “At” and “on” may be when? or where? and if “even though” does not mean “if”, in which case it would be under what conditions?, then it means but how about? is the question.

4. "That” is almost always what?

5. There are a few exceptions to the other four rules.

So when approaching a question, there are four questions to ask:

1. How many pieces?

2. Which is set?

3. Which are companions?

4. Surely it must be time for supper soon, isn’t it?

Finally, application. There are:

· 5 questions I ask myself

· 7 principles

· 14 golden rules

· 6 “don’t’s”

· 8 “do’s”

· 5 “this is possible but check with your Fellowship Group leader first”

So, to demonstrate:

(At this point another member of the course took over to do something, the content of which is perhaps mercifully lost to posterity…)

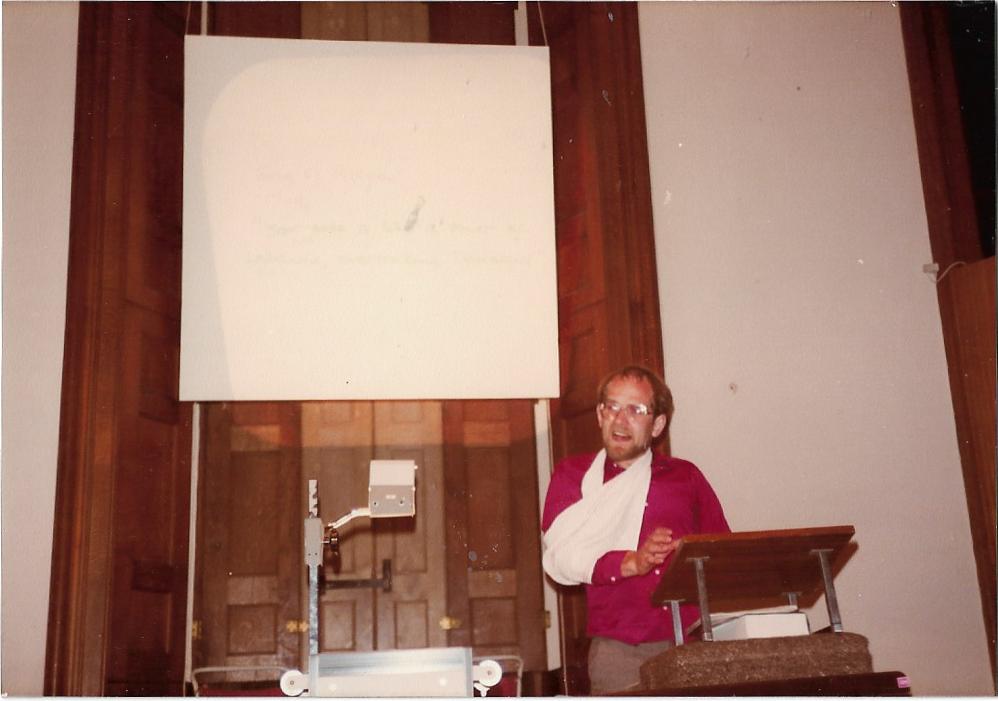

Given at a weekend away for Core Year, the theological training course developed and run by Andrew Cornes at All Souls, Langham Place. I think the event was at Ashburnham Place in Sussex in 1983. A good deal of the course was taken up with Andrew’s Basic Method of Bible study, of which this is both tribute and parody. Andrew had a reputation as a lover of food and fine art, and used illustrations from the latter in his teaching. Andrew had recently broken his arm and all those taking part in the entertainment wore slings in arcane homage. Core Year was hugely influential on the rest of my life, as doing the course at the same time was Tessa Duckworth, who lived not far from me in west London and who I used to give lifts home to and subsequently married.